|

Here is a mash-up of Allen Ginsberg's poem "America" with a couple of songs by M83 and Broadcast. You have to click through a few pages to download it. Courtesy of this free audio editing program, and an audio glitch in my computer that gave me the idea. All works copyright of their owners. (If any license holders wish this file to removed, please contact me.)

The Times has released the 100 Notable Books of the Year.

And, here is my beautiful girlfriend on the left, winning first round of the Christ Church Regatta 2005, rowing for Magdalen College.

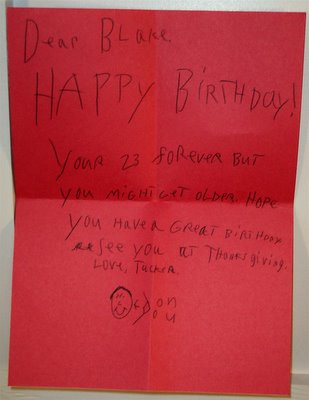

I love the way my brother's mind works. These kinds of non sequiturs just fall out of him. He's ten.

And here are some pictures from today from Central Park. I went to catch the last of the fall leaves, a la the final scene of Angels in America, which you should drop everything today to rent and watch. Seriously.

I'm not really that sorry.

One could also call conservatism (more favorably) an allegiance to facts. William F. Buckley, the famous conservative who founded National Review, calls conservatism “the acknowledgment of realities.” One could stretch that to include the aim of science, to rely on verifiable ideas and a suspicion of too much ideology. In an excellent New Yorker article about Peter Viereck and the origins of modern conservatism (which, back then, was something that I could relate to), Buckley was asked about today’s Bush conservatives and conservatism’s current course. “I’m not happy about it. It’s probably true that in [support for the war in Iraq] you have a rediscovery of idealism. It’s not, in my judgment, conservatism. Because conservatism is, to a considerable extent, the acknowledgment of realities. And this is surreal.”

The war in Iraq and the ideal of spreading democracy is separate from the skewed moral mission of Republicans on social issues, but the strangely unbalanced emphasis on certain aspects of traditional values along with a disregard for others is shared by both. In the New Yorker article, Viereck speaks about why he reacted so strongly against Mcarthyism and the resulting conservatism: “What causes the greatest crimes in history? The greatest bloodshed? The most murders? I would say two things: sincere love and a sincere devotion to liberty.” Viereck was referring to the utopian aims of communism, that if one focuses too strongly on an abstract idea, one will end up sacrificing others: this is a good rough outline of fundamentalism. It is faith carried too far, when its worst qualities are emphasized. It is the infusion of religion and politics, which is central to the situation in Kansas.

As the NYTimes article mentions, the conservative movement is the one trying to redefine something longstanding, when that’s what, usually, the left has tried to do. The roles have been strangely reversed.

This is interesting:

When pressed for a definition of what they do, many scientists eventually fall back on the notion of falsifiability propounded by the philosopher Karl Popper. A scientific statement, he said, is one that can be proved wrong, like "the sun always rises in the east" or "light in a vacuum travels 186,000 miles a second." By Popper's rules, a law of science can never be proved; it can only be used to make a prediction that can be tested, with the possibility of being proved wrong.Intelligent Design can never be proved wrong, even as it claims to prove Evolution wrong (or at least inadequate). It points to a vacuum in our understanding and fills it with something that does the aim of Science no good. It’s actually a kind of laziness.

Having grown up in an Evangelical household, I have been involved with this issue for a long time, and read a few books which promoted Intelligent Design when I was young, including Michael Behe’s Darwin’s Black Box. I even wrote a research paper in 8th grade on why Evolution was inadequate. But when I look back, the whole thing rings false: I wasn’t concerned with science when I was reading the books or writing the paper--I wasn’t looking at Darwin’s writings or current scientific defenses, except as they were mentioned and quickly refuted in the anti-evolution books. What I was really writing about was religion, in a roundabout way, and the answer to the questions of origin were already in mind. Ideology remained deeper and more important than curiosity and, eventually, facts. I wasn't a scientist, but I felt comfortable making sweeping and obviously controversial scientific claims. (From an Amazon review for the book: "What I like so very much about this book is that very complicated ideas are simplified to my level. So, if you're not a scientist, don't worry...I can still quote his nine year old material to refute what evolutionists say. --Sean Horton, "the bibliophile").

The philosopher Jean Mercier writes that “Fundamentalists read their own books and none other; they consider knowledge from other sources useless and dangerous since it creates only doubt and confusion. It is enough to surrender unconditionally to the letter of ‘The word of God’” But the Bible and other religious texts are slippery things, easily appropriated and interpreted to satisfy the reader--whether it is to reinforce one’s own beliefs, or to condemn others'. “Bible readers...search the Bible for themselves,” Harold Bloom writes. One can find the evidence for any system of belief or doubt in too many places to count.

“I can think of nothing more gallant, even though again and again we fail, than attempting to get at the facts; attempting to tell things as they really are. For at least reality, though never fully attained, can be defined. Reality is that which, when you don’t believe in it, doesn’t go away.” Viereck’s resolve is inspiring and infectious; he is speaking, I think, about a kind of marriage of idealism and science. A relationship in which the former is tempered by the latter, yet the idealism continues to inspire the quest. There is a push and pull, a carefully orchestrated and sacred balance, a restraint and a desire to leap. Progress happens when both are kept in check.

For, throughout his own imaginative writing, Lewis is always trying to stuff the marvellous back into the allegorical—his conscience as a writer lets him see that the marvellous should be there for its own marvellous sake, just as imaginative myth, but his Christian duty insists that the marvellous must (to use his own giveaway language) be reinfected with belief. He is always trying to inoculate metaphor with allegory, or, at least, drug it, so that it walks around hollow-eyed, saying just what it’s supposed to say. [...]

“Everything began with images,” Lewis wrote, admitting that he saw his faun before he got his message. He came to Bethlehem by way of Narnia, not the other way around. Whatever we think of the allegories it contains, the imaginary world that Lewis created is what matters. We go to the writing of the marvellous, and to children’s books, for stories, certainly, and for the epic possibilities of good and evil in confrontation, not yet so mixed as they are in life. But we go, above all, for imagery: it is the force of imagery that carries us forward. [...]

For poetry and fantasy aren’t stimulants to a deeper spiritual appetite; they are what we have to fill the appetite. The experience of magic conveyed by poetry, landscape, light, and ritual, is . . . an experience of magic conveyed by poetry, landscape, light, and ritual. To hope that the conveyance will turn out to bring another message, beyond itself, is the futile hope of the mystic. Fairy stories are not rich because they are true, and they lose none of their light because someone lit the candle. It is here that the atheist and the believer meet, exactly in the realm of made-up magic. Atheists need ghosts and kings and magical uncles and strange coincidences, living fairies and thriving Lilliputians, just as much as the believers do, to register their understanding that a narrow material world, unlit by imagination, is inadequate to our experience, much less to our hopes.

The religious believer finds consolation, and relief, too, in the world of magic exactly because it is at odds with the necessarily straitened and punitive morality of organized worship, even if the believer is, like Lewis, reluctant to admit it. The irrational images—the street lamp in the snow and the silver chair and the speaking horse—are as much an escape for the Christian imagination as for the rationalist, and we sense a deeper joy in Lewis’s prose as it escapes from the demands of Christian belief into the darker realm of magic. As for faith, well, a handful of images is as good as an armful of arguments, as the old apostles always knew.

This Toronto-based photography runs a daily photoblog, and the photos are consistently interesting and strikingly beautiful. This one is not indicative of his usual style, which is often an interest in architecture: it's potential to be reappropriated, its relationship to nature. But they all have a great sense of unsentimental, non-clichéd whimsy, which is a rare thing. This was too funny to pass up. Read carefully. (click to enlarge)

Strangely, one enters a space which is normally abstract, computerized, unhuman, digital--if you let yourself become absorbed and entranced by the play of color, you feel as if you are in some theoretical, pixelated world; there is a loss of the sense of the body. It’s a sort of virtual-reality space, but, importantly, it’s a low-tech one: the pixels are couple feet square, improbably large, as if the image is of bad resolution, antiquated.

I immediately associated this low-fi experience with grainy, blown-up photography, which has a negative connotation, one of dimly-lit, forbidden revelations: the photographs of prisoner tortures at Abu Ghraib, of underground porn, old mug shots, celebrities topless on a beach caught by the paparazzi. Strangely, I associated immorality with poor quality images; on the converse, then, fidelity is morality.

Bullock plays with this idea in another work, my favorite in the show, in which she projects a grainy, black and white off-putting photograph of a crowd of people who are either singing or screaming--both seem plausible--onto the gallery wall. It is clearly an old image, and it feels like something out of Schindler’s List. In a deft move, she places the projector around waist-level, so that one sees the grainy photograph and moves closer, but can’t help eclipsing the image’s projection, casting a shadow of ones body over the contorted faces. Importantly, ones images is sharp and defined, while at this close distance, the photograph is so pixelated as to border on abstraction. On a nearby wall is a printed version of the same photograph with someone’s shadow over it in the same way. That person is clearly a conductor with passionate, outraised hands--a classic image of a choir with the shadowed outline of a conductor in the foreground. I turned back to the projection, and hoped that the people in the grainy photograph were indeed singing. The way the viewer’s outline is so sharp and the photograph so grainy that the moral and immoral associations of each are compelling: as conductor, am I to feel pathos, fear, joy? Am I the cause of what seem like such abnormally emotional faces? Am I a dictator, or an inspiration? Are those blurred images, which have been abstracted and lack clean lines, still representations of humanity?

On a simpler and less interpretive scale, the art Bulloch makes is highly successful in altering and disrupting the viewer’s perception, with a focus on emphasizing or dissolving the body. She seems to confront the membrane which separates actual physical space and conceptual or digital reality, making the viewer aware of how each carries its set of principles, and the interactions between those worlds is inevitably moral. She says in the catalog interview that the work depends on the viewer, not to explicitly interact, but to be “inter-passive” (versus inter-active). There are no buttons to push or levers to pull, but the viewer’s engagement with the work “is discovered the moment the work is completed by the presence of the viewer.” What I like about this distinction is the way it gives high regard to this inhuman, otherworldly space: the way we often interact with the digital realm is to push buttons and pull levers; in her art, we need only confront it morally. Is it something that we created, but now exists on its own terms?

It’s been a whirlwind trip, a weekend in Oxford, one in which the shock of jet lag (not to speak of adjusting) kept me confused about my thoughts and identity on a pretty consistent basis. Along with the fact that this confusion and missing identity was already the case all of last week (I'll say that without expanding), as time winds down on this Sunday evening/morning things are slowly coming into focus. Creamy espresso helps. So does The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan.

It was a brilliant blue sky on Friday there, which was surprising both because one expects clouds in England, and because every other time I’ve been to a famous university, it’s been gray. Saturday the clouds showed up for the afternoon, and today it rained.

I’m talking about the weather, which is boring. It was a needed weekend. I left New York and my own recently obsessive solipsism with it, and tagged along with E., getting a sense of her life there, her friends, and how much her life revolves around the newly-acquired sport of rowing. Met all the friends who are an extension of that sport, along with a few others. There’s a lively spirit there, not the reserved intellectualism that I somehow imagined. It felt enlivening to be back in Europe in the British Isles, back in Oxford after a short visit last time. There’s a smell to it, something, a cheekiness to conversation and lots of up-beat ways of saying words, placing the accent at the end. I find myself automatically adopting the way of speaking, which I noticed that I do even with foreign accents while I was traveling in Europe. We would be in Italy, and if I was trying to communicate with an Italian I would speak English with a sort of Italian accent, as if that would make it easier. I am trying to figure out if that approach is empathetic or imperialistic.

This new Virgin Atlantic plane feels really strange: all the lights are white halogen, quite cold, and the bathroom is spacious and lit with blue light. It feels like a nightclub.

About me

- Blake

- Chicago, IL, United States

Recent Posts

- 2007 Albums

- 2006 albums

- On Buying Books

- From a Style Manual Directed at Freshman Year Writ...

- Umberto Eco on the Holy War of Mac vs. PC

- What was happening in your hotel room the day befo...

- A Pretentious Dialogue on Borges and Judas and a P...

- Literal meaning = death

- A conversation about art between Austin and I, dru...

- Why fundamentalism often sounds the same regardles...

The Paupered Chef

- The World is Our Porkchop

- An American Infant in Japan

- A Foot in Each World

- Temporarily

- Born in Kansas

- The Mixtape

- Duncan

- The Vulgate of Experience

- Distressful Tidings

- The Red Pen is the Mightiest

- Sincerely, Alexander

- Late Twenties

- Conversational Reading

- The Morning News

- Identity Theory

- The Syntax of Things

- The Beiderbecke Affair

- Inhabitat