|

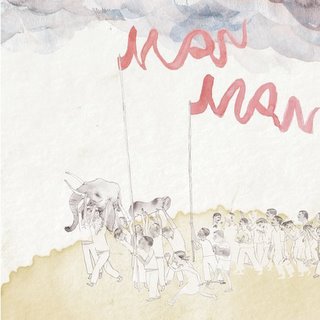

Man Man’s album Six Demon Bag is one of the more engaging things I’ve listened to in awhile. The kind of complete gimmickry and insanity that makes it impossible to just put on in the background. It veers toward being eclipsed by its own tricks and stunts, but it’s a good album nonetheless. Sounds kind of like Animal Collective if they suddenly underwent a moodswing from nostalgic to angry, switched from LSD to cocaine, and joined the circus.

Man Man’s album Six Demon Bag is one of the more engaging things I’ve listened to in awhile. The kind of complete gimmickry and insanity that makes it impossible to just put on in the background. It veers toward being eclipsed by its own tricks and stunts, but it’s a good album nonetheless. Sounds kind of like Animal Collective if they suddenly underwent a moodswing from nostalgic to angry, switched from LSD to cocaine, and joined the circus.And, this is mostly unrelated: How bad is Derrida for our intellectual climate and institutions? Postmodernism, specifically deconstructionist ideas, is touted as a big bad wolf, the kind of catch-all representative for all that's-wrong-with-our-culture, especially in regard to religion. This article argues it differently and insightfully. At the extremes of postmodernism there is total relativism which ends up with conclusions that are hostile towards religion. Here many bring up the question "What is true, then?" or suggest that "If nothing is right or wrong, and everyone is right, we have indifference or even chaos." What the article points out is that all this deconstruction, this pointing out of gaps and inconsistencies and problems with truth and meaning, ends up with what Derrida later termed the “undeconstructible,” a concept that's hard to describe. Derrida said that justice, for example, is indeconstuctible--it is, of course, still a word, but Derrida explains it this way, in the midst of a discussion involving the story of Babel: "the place that gives rise and place to Babel would be indeconstructible, not as a construction whose foundations would be sure, sheltered from every internal or external deconstruction, but as the very spacing of de-construction." Meaning it isn't that justice is out of bounds of deconstruction, but that it has in its definition a structure which don't create the usual loop of oppressive self-referential signifiers.

Essentially it is some thing that is pure affirmation, something that is beyond the reach of decontructionism and therefore beyond our abilities to reason and even imagine. Kind of a desire beyond desire itself. In this sense Derrida's entire project was making an affirmation rather than a negation—an important point. From Sauf le Nom:

Here the invisible limit would pass less between the Babelian project and its deconstruction than between the Babelian place (event, Ereignis, history, revelation, eschato-teleology, messianism, address, destination, response and responsibility, construction and deconstruction) and 'something' without thing, like an indeconstructible Khora, the one that precedes itself in the test, as if they were two, the one and its double...

The "Khora" can be defined as something it is not--it is something that defies the logic of noncontradiction, the either/or dichotomy. The article suggests that Derrida's deconstruction really is a kind of extremely high standard, an idea that is akin to, for example, the Jewish rejection of idols as inadequate and inappropriate. Maybe postmodernism can be friendlier to religion than we think. Actually, there are some fascinating parallels. Certainly, by definition it doesn't have to be, and we would do well to understand it more fully before seeing the whole thing as one big hostile empire.

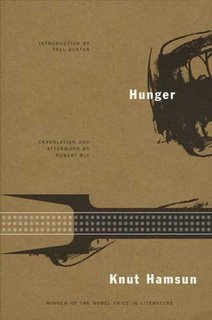

"He fasts. But not in the way a Christian would fast. He is not denying earthly life in anticipation of heavenly life; he is simply refusing to live the life he has been given...hunger, which opens the void, does not have the power to seal it up." --Paul Auster, from The Art of Hunger.

This book is a flat-out masterpiece, a novel of inwardness, narrated by a character who has found himself, on purpose or by chance, at the outskirts of society. He has come to the city to write, but cannot write. He starves because he cannot write, and cannot write because he is starving. In this edge there is solitude, the shadow of potential insanity, and the limits of physical hardships: coldness, hunger. There is also serenity and artistic clairvoyance.

The novel was written in 1890 and is drawn from ten years of Hamsun’s hardships living as a struggling writer, condensed and rearranged. It is an empty novel, empty in the sense that its plot, action, scenes, and characters are never materialized outside of the narrator’s head.

Most compelling is what Robert Bly calls in the afterword a calmness (really: indifference) towards both the social or moral ramifications of a man going hungry with no one to help him, and towards the hysterical impulses a body will have for physical needs. Further, the narrator has no interest in judging those “demonic impulses” right or wrong: what fundamentalists and disciples of de Sade have in common is an obsession with natural human (fleshly) impulses. The narrator sees them come and go and does something akin to befriending them, to observing them pass and refusing hysteria. He watches himself deteriorate and approach insanity with a sanguine affection. For this reason, Bly suggests that “the book then is morally at odds with a great deal of Western literature”. The narrator is nonetheless honest, and randomly gives away a sum of money which he comes upon by a clerk giving him too much change from a transaction. Yet other times he lies for no reason, creates fictions to separate himself from the world, usually to convince others that might help him that nothing is wrong. There is a conscious separation of these other impulses, impulses for sex or food, into some separate category, objectifying them and turning them (their denial) into art. Morality can have no place there.

About me

- Blake

- Chicago, IL, United States

Recent Posts

- 2007 Albums

- 2006 albums

- On Buying Books

- From a Style Manual Directed at Freshman Year Writ...

- Umberto Eco on the Holy War of Mac vs. PC

- What was happening in your hotel room the day befo...

- A Pretentious Dialogue on Borges and Judas and a P...

- Literal meaning = death

- A conversation about art between Austin and I, dru...

- Why fundamentalism often sounds the same regardles...

The Paupered Chef

- The World is Our Porkchop

- An American Infant in Japan

- A Foot in Each World

- Temporarily

- Born in Kansas

- The Mixtape

- Duncan

- The Vulgate of Experience

- Distressful Tidings

- The Red Pen is the Mightiest

- Sincerely, Alexander

- Late Twenties

- Conversational Reading

- The Morning News

- Identity Theory

- The Syntax of Things

- The Beiderbecke Affair

- Inhabitat